THE BIRTH OF

A DIVISION

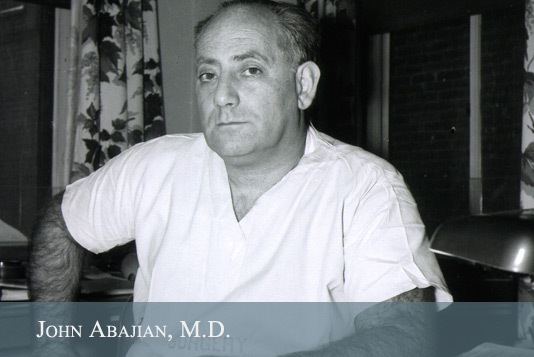

After Ford left,

John Abajian came

to Burlington with

a directive to create

a department for

anesthesiology at Mary Fletcher Hospital. A city boy who

attended Long Island University and New

York Medical College, Kreutz notes that

Abajian arrived in Vermont feeling like he

had been “banished to Siberia.” He quickly

earned a reputation as both brilliant

and difficult.

Almost immediately, some members of the

UVM medical staff were put off by Abajian’s

personality: cocky, opinionated, and extremely

outspoken, he made enemies easily. It turned

out that he was a very good anesthesiologist,

though, and he “managed to survive the next

few months.” Soon “known and admired by

the surgeons for his great intellect, innovative

ideas, and capable performance of his duties,”

Abajian later credited some of them — Al

Mackay, Walford “Wally” Rees, Keith Truax,

Lyman Allen, even old George Sabin — with

helping him through his turbulent first year in

Burlington. He also singled out T.S. Brown, who

became “like a second father” to him, saying:

“The only thing I really regret now is that I

wasn’t born a Vermonter. The type of cooperation

I received from people at the Fletcher at that

time, and from the medical school, is the best

any anesthesiologist could obtain and receive

anywhere in the United States.”

Abajian soon

recruited 24

year-old nurse

anesthetist

Elizabeth “Betty”

Wells to his

newfound division.

The techniques

they used where “atypical for the era,” Kreutz notes, with

a focus on local and regional anesthesia.

Although it’s unclear why he preferred these

methods, the duo continued to shape the

practice of anesthesiology through their

partnership. Wells later proved to be

indispensable, as World War II began to

call men into military service.

JOHN ABA JIAN GOES TO WAR

Abajian enlisted in the U.S. Army in 1942,

and headed off to war. He eventually became

consulting anesthesiologist to General

George Patton, traveling throughout the

European Theater teaching nurses and

physicians in the field “fundamental

anesthesia techniques, pre-and postoperative

care, and shock and transfusion therapy.”

Kreutz says Abajian focused on regional

and local anesthesia as opposed to general,

just as he had done in Vermont. His work

is credited with saving many soldiers’ lives.

Abajian enlisted in the U.S. Army in 1942,

and headed off to war. He eventually became

consulting anesthesiologist to General

George Patton, traveling throughout the

European Theater teaching nurses and

physicians in the field “fundamental

anesthesia techniques, pre-and postoperative

care, and shock and transfusion therapy.”

Kreutz says Abajian focused on regional

and local anesthesia as opposed to general,

just as he had done in Vermont. His work

is credited with saving many soldiers’ lives.

George Patton’s Army was the epitome of a

hard charging, hard hitting, mobile warfare

unit, but it endured tremendous losses in

the process — from August 1944 through

April 1945, it suffered over 91,000 battle

casualties. During that period its overall

mortality rate fell significantly, though, from

2.9 percent in mid-1944 to 2.6 percent in

1945, and it’s possible that John Abajian’s

work at field and evacuation hospitals was one

of the reasons for the improvement. Patton

may have thought so, for he recommended

Abajian for the Legion of Merit. Odom also

credited Abajian for his “most useful” work,

writing in a postwar summary:

“By the time Major Abajian left a unit, he

had succeeded in giving valuable instruction in both the theory and practice of the

administration of anesthetics and had also

given valuable assistance in the handling of

casualties in the operating room. His work

elevated the standards of both anesthesia

and surgery in the Third U.S. Army.”

Abajian returned to the United States in

June of 1945 at the rank of Lieutenant

Colonel, and resumed his position at

UVM at the start of 1946.

THE HOME

FRONT

With Abajian

traversing Europe

with Patton’s

Army, back in

Vermont, Wells

became the leader

of the new division

at 25 years-old, caring for patients with

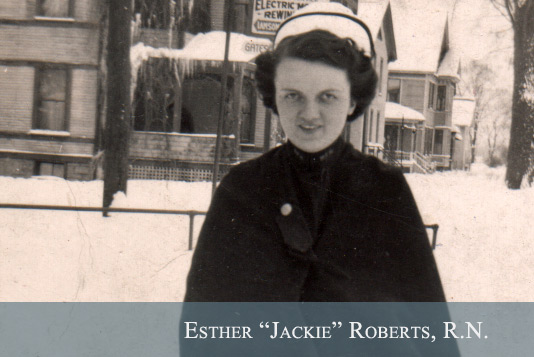

tireless dedication. She was joined by another nurse, Esther “Jackie” Roberts,

whom Kreutz describes as a “plain-spoken

farm girl from Barnard, Vt.,” and internist

Christopher Terrien Sr., a 1936 grad of the

UVM College of Medicine. The young

team handled the situation with remarkable

grace, according to Kreutz’s reporting.

Despite the workload and risks, Wells later

wrote, “We survived the frequent call schedule

and, more importantly, our patients did too.

There were no fatalities due to anesthesia

during that period — I probably would have

resigned if there had been.” But by 1944, Wells

and Roberts were worn out and asked Mary

Fletcher Hospital’s new Superintendent, Lester

Richwagen, for more help. He obliged, hiring

Mary Fletcher School of Nursing graduates

Frances Wool in May 1944 and Florence

“Peg” Thompson in January 1945.

As World War II wound down, and

anticipating the return of many young men

seeking employment, the nurse anesthetists

who had put in countless long days and

call hours caring for patients during the war

explored their career options.

Kreutz notes that Wells and Thompson

continued to work in anesthesiology,

while Wool joined the military before

serving as a private nurse in New

Hampshire. Roberts found success in a

different medical field — she went on

to serve as surgical assistant to eminent

UVM neurosurgeon R.M.P. Donaghy,

who pioneered microsurgery, and in

1969, she was honored as the “Mother of

Microneurosurgery.” She died in South

Burlington, Vt., in 2010, at the age of 90.

BUILDING A DIVISION

With men returning from the war eager

for additional training and employment,

a postwar directive from the American

Medical Association urged “hospitals

around the country to expand their postwar

residency programs.” With a Division

of Anesthesiology once again under the

leadership of Abajian, UVM did just that,

setting up a residency program and hiring

its first anesthesia resident, Antonio Bayuk,

in July of 1946. A veteran who had been

injured in a parachute jump in Germany, he

was soon joined by a second resident, Ernie

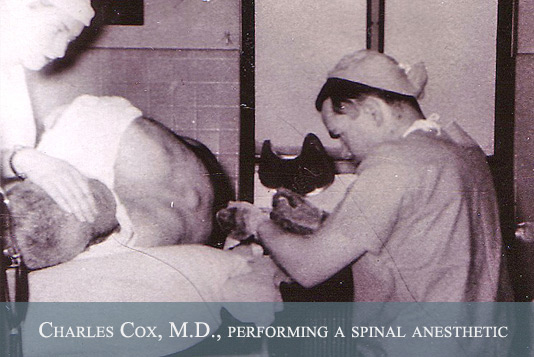

Mills, also a veteran. Additional residents

followed, including Donald Harwood and

Charles Cox. These early residents recall

both the challenges and the rewards of

working in a rapidly changing field.

Anesthesia was still a relatively dangerous

business in the early 1950s, with primitive

agents (ether and cyclopropane) and

crude monitoring (primarily a “finger on the

pulse”), but the residents learned to deal

with it. “Safety was primordial,” according to

Francesca deGerman. “This is why we used

local, blocks, spinals, continuous spinals, and

general anesthesia, in that order.” Harwood

remembered that he “learned to be suspicious

of redheads and fast-pulsed patients.” Cox

noted that he didn’t lose a single patient during

his residency, a remarkable achievement.

Betty Wells and Ernie Mills did most of the

teaching that took place. “Betty and Ernie and

dear experience were our mentors,” Harwood

recalled:

“I learned that we would be integrated

into the thick of things very rapidly and it was

sink or swim…. John gave us an unfettered

opportunity to get into trouble on our own and

get back out of it if we could…. [He] helped

us cultivate intuition.”

These first residents helped to lay the

foundation for a robust division that

would go on to make some important

discoveries in the field.