Do the cognitive changes that sometimes occur at menopause relate to an increased risk for Alzheimer’s disease? That’s what a newly launched study, co-led by University of Vermont Associate Professor of Psychiatry Julie Dumas, Ph.D., aims to determine.

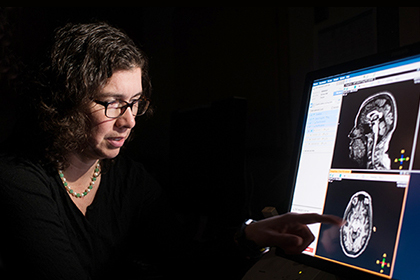

UVM Associate Professor of Psychiatry Julie Dumas, Ph.D., examines a study participant’s MRI in the Larner College of Medicine’s MRI Center for Biomedical Imaging in the UVM Medical Center. (Photo: Andy Duback)

Do the cognitive changes that sometimes occur at menopause relate to an increased risk for Alzheimer’s disease (AD)? That’s what a newly launched study, co-led by University of Vermont Associate Professor of Psychiatry Julie Dumas, Ph.D., aims to determine.

According to the Alzheimer’s Association, almost two-thirds of Americans with AD are women. While previous research has shown that some, but not all, women experience a change in cognition at menopause, to date, no research has linked these menopausal cognitive changes to risk for late life aging-related diseases including AD.

One of the challenges for determining this link is what Dumas describes as a “long lag time between the hormonal changes at menopause and the clinical manifestations of AD.” She and her co-principle investigator, Paul Newhouse, M.D., director of the Vanderbilt University Center for Cognitive Medicine, are experts on the role of estrogen in the brain’s cholinergic system, which is responsible for cognitive processing.

Preclinical studies have shown that estrogen — a hormone produced by the ovaries that is made in significantly less quantities following menopause — is necessary for normal functioning of the cholinergic system. When estrogen is withdrawn, it can lead to a dysfunction in this system, resulting in cognitive impairment.

With the support of more than $7 million in funding from the National Institute on Aging, Dumas, Newhouse, and their research teams will examine biological, brain and memory changes in normal postmenopausal women to determine whether they may be connected to abnormal aging patterns later in life.

“We will use state-of-the-art tools like MRI, positron emission tomography (PET), and novel analysis of proteins in the blood to ask our research questions about cognition after menopause and risk for AD,” says Dumas. “There are likely many individual differences in these biomarkers for each woman that may or may not be related to risk for AD. We hope we can start to tell that story through the results of this study,” she adds.

If these cognitive changes are found to influence a woman’s risk for cognitive decline, the results could help explain why the prevalence of Alzheimer’s disease is higher in women than in men. It could also lead to sex-specific prevention and treatment strategies.

Currently, the UVM research team is conducting telephone screenings and educating potential study participants about the research. To request more information, email menopauseandbrain@uvm.edu.

(Portions of this article were adapted from a Vanderbilt University Medical Center article by Kelsey Herbers.)